In the annals of warfare, few units are as storied as the American Eighth Air Force during World War II. It’s estimated that 350,000 men served in the Mighty Eighth during the war. One of them was Lt. Francis Witt, assigned to the 384th Bombardment Group as a pilot of a B-17 Fighting Fortress. With a crew of 10 men, up to 13 machine guns, and a typical bomb load of 4,000 pounds, she was the backbone of the European strategic bombing campaign against Germany.

After flight training in the United States, Witt arrived in June 1943 at United States Army Air Field 106, more popularly known as RAF Grafton Underwood, outside Kettering, Northamptonshire, England. Grafton Underwood, before World War II, was largely farmland, but the Nazi invasion of France in 1940 and the subsequent bombing of England meant additional airfields were needed to first launch aircraft to defend Britain and then offensively strike targets throughout the European continent. Initially assigned a Royal Air Force squadron, Grafton Underwood was one of a number of bases turned over to the Army Air Force beginning in 1942 after the United States joined the war. (In fact, RAF Grafton Underwood launched the first USAAF bombing mission against the Nazis when then-Captain Paul Tibbets, later known for dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, led a bombing mission against a train yard in Rouen, France.)

Although he arrived at Grafton in June 1943, an accident while landing during a training flight kept Francis grounded until October. It was just as well, anyway. September and October 1943 represented a rebuilding period for the B-17 groups in England. Two August 17 raids to bomb the industrial cities of Schweinfurt and Regensburg in Germany had cost 60 of the 376 participating bombers. With an average crew of ten, that represented over 600 aircrew killed or missing in action. While Francis didn’t fly this mission, his 384th Group lost five of the 20 planes that launched to enemy action. So while the missions continued after – bombing runs to submarine pens in France and German airfields in Belgium – none included as many aircraft or were as complicated an operation as the August 17 mission.

That would change on October 14 when the 8th Bomber Command, the bombing arm of the famous 8th Air Force, identified the ball bearing plants of Schweinfurt as once again needing to be bombed. The mission was theoretically simple. A massive armada of American bombers would fly to Schweinfurt and, at the appointed moment, drop their bombs over the target. Anyone who has seen the films 12 O’Clock High or Memphis Belle, however, knows it’s not that simple. Aircrews faced murderous and accurate flak from the ground and German fighters numbering in the hundreds. Meanwhile, American “little friends,” as the P-47 Thunderbolts were called by the bomber crews, lacked enough fuel to go all the way to the target. As soon as they departed, the German fighters jumped. The aircrews knew the odds for their return were never great.

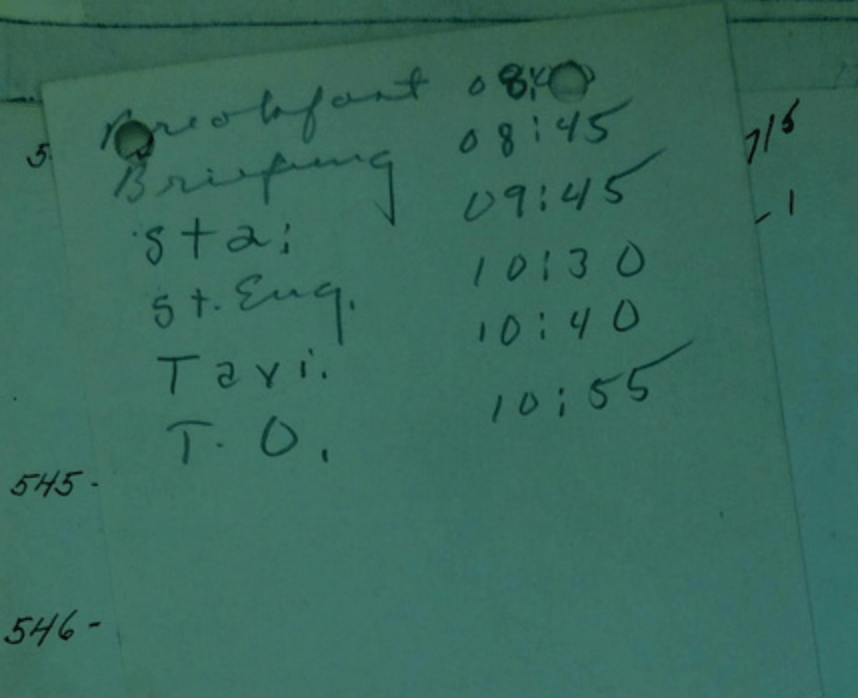

On the morning of the 14th, Francis was likely asleep in his steel Nissen hut with seven other officers when an enlisted man came to wake him up. “Good morning, sir; you’re flying today as co-pilot for Flight Officer Carter in ship 525, What’s Cookin’ Doc. Breakfast at 0800. Briefing at 0845.”

As the officers filed into the briefing room, there was a curtain covering the location to be bombed, but as the briefing started and the curtain was removed, audible groans would have gone up as “SCHWEINFURT” was announced. The men in the room all knew what happened last time. The briefing would have provided the operational details of the mission. An operations officer would have given the flying route, the levels of enemy flak and aircraft expected, and the secondary targets available if weather socked in the primary. A meteorological officer would have briefed the expected weather conditions. The Group’s chaplain was likely hanging out in the back or just outside the briefing room to bless the airmen as they exited or provide one last absolution before going up and maybe not coming back. Then, piling into a jeep, the men were carted to the other side of the airfield to the fleet of waiting B-17s sitting on the hardstands. Greeting the crew chief, Carter and Witt were briefed on any mechanical issues he had to troubleshoot or repair overnight.

The crew for the mission was:

| Pilot | Carter, T L |

| Co-pilot | Witt, Francis John, Jr |

| Navigator | Garrison, Keith M |

| Bombardier | Smith, Harvey Daniel |

| Radio Operator | Benson, Thomas Joseph |

| Engineer/Top Turret | Treat, Royal DeWitt |

| Ball Turret | Connelly, Gordon Raker |

| Tail Gunner | Pastorella, John Paul |

| Waist (Flexible) Gunner | Barto, Louis Joseph |

| Waist (Flexible) Gunner | Hubbard, Warren Emmett |

At 1030, it was “start engines,” and the airfield came to life as three squadrons worth of aircraft, twenty-one in all, sputtered, spurted, and then roared with the spinning of 84 Wright Cyclone engines. Taxiing en masse and taking off less than a minute apart, the whole fleet of 384th bombers would be airborne in about 20 minutes. The 384th bombers would join up with the other groups in the skies of southeast England, with 291 aircraft in all heading to Schweinfurt in an attempt at crippling the German ball bearing production.

The B-17 flying over England would form “combat boxes” in the sky to ensure a tight formation but allow each bomber the space to drop its load unencumbered. Francis’s B-17 was flying in the high group for the Schweinfurt mission. This was always the preferred spot in the box; lower groups tended to make for easier targets for enemy aircraft and flak.

The 291 bombers flying to Schweinfurt that day relied on their escort fighters for protection, but the P-47 fighters departed their bigger cousins after about 200 miles. From bases all over France, Belgium, and Germany, the Luftwaffe struck with the typical tactic employed of German fighters flying directly at the bombers. They would lay a short burst of close, murderous fire right where it would cause the most harm – into the pilots. Bombers would fall from the sky with their dead pilots as the remaining eight members of the aircrew attempted to fight the G forces of an out-of-control aircraft and jump before the plane exploded into the ground. After the German fighter ran head-on into the bombers, they’d come back from behind, firing explosive rockets into the formation. While inaccurate, a single lucky strike could take down a bomber or, at worst, force the formation to take evasive action, separating them and making them more susceptible to gunfire.

All of this hell unfolded in front of Francis as he and Carter guided their B-17 over the target. After “bombs away,” it was a sharp turn to the right and a small slice of hope they make it home. The enemy aircraft and flak, however, would remain for 200 miles of the return. Only over Belgium would the P-47s return to provide cover for the last leg home. The odds were stacked against the crews as rain and low cloud cover typical of England in the winter socked in Grafton Underwood. Many of the 384th planes couldn’t find the airfield. Three planes were lost, and their crews bailed when they started running out of fuel. Carter and Witt would not make it back to Grafton, taking What’s Cookin’ Doc and the eight other men inside it to RAF Little Staughton, a B-17 repair depot.

Sixty of the 291 bombers that launched for Schweinfurt were lost to enemy action. Another dozen were scrapped due to damage. Six hundred men were captured or killed in action. In Witt’s 384th Group, six aircraft went down. Lt. William Harry’s B-17, ME AN’ MY GAL, was shot down by German aircraft. His co-pilot and bombardier were killed, while Harry and seven others were captured as POWs. In the ship flown by Lt. Lawrence Keller, Sad Sack, everyone in the front of the aircraft – the two pilots, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, plus the ball turret gunner, were killed, likely victims of the German head-on assault. Four men jumped in their chutes to become POWs. Lt. William Kopf’s The Joker exploded over Belgium, with seven killed. Lt. Giles Kauffman’s B-17, Big Moose, went down near Brückenau with nine POWs. A gunner, Sgt. Peter Seniawsky, evaded capture and made it back to England. Lt. Walter Williams and Lt. David Ogilvie’s crews were fortunate. Of the twenty men, only one was killed. Nineteen either evaded capture or spent the rest of the war as POWs.

As historian Donald L. Miller would later write in Masters of the Air, a comprehensive study of the Eight Air Force in World War II (and soon-to-be AppleTV+ miniseries), “The deep penetration raids against Schweinfurt’s ball bearing complex should not have been mounted until a larger bomber force was assembled and protected by long-ranger fighters. In miscalculating the ability of the unfortunately named Fortress to stand up to the Luftwaffe, American air planners needlessly sacrificed the lives of young men who were unable to fully appreciate the desperate nature of their missions.” (p. 469)

Sources:

This article could not have been completed without the resources, images, and databases of the 384th Bomb Group, Inc.

384th Bombardment Group Association, Inc., (https://384thbombgroup.com : accessed 13 Jan 2024), used the mission profiles, crew profiles, and images databases.

““Black Thursday” October 14, 1943: The Second Schweinfurt Bombing Raid,” The National World War II Museum, (https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-thursday-october-14-1943-second-schweinfurt-bombing-raid : accessed 13 Jan 2024).

Blackwell, Wally, “398th Bomb Group Combat Formations,” 398th Bombardment Group Memorial Association, Inc., (http://www.398th.org/Research/8th_AF_Formations_Description.html : accessed 13 Jan 2024),

“Combat Box,” Wikipedia, (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combat_box : accessed 13 Jan 2024).

“Little Stoughton,” Bomber Command, Ministry of Defence, (https://web.archive.org/web/20121026084305/http://www.raf.mod.uk/bombercommand/s101.html : accessed 13 Jan 2024), Wayback version of website, version updated 6 Apr 2005, 2:40 AM.

Miller, Donald L. “Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War against Nazi Germany,” Simon & Schuster, 1st printing, New York, 2006.